Summit Labs Canadian Lakes Management

The Summit Labs Canadian Lake Management Blog was created to provide Canadian Lake Riparian owners better access to us, their lake managers. Communication is essential in successful lake management. Efficient communication allows us to maximize our time managing while satisfying riparians questions and concerns.

Friday, June 24, 2005

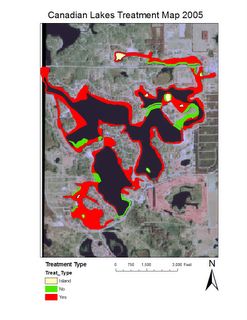

The 2005 General Herbicide Treatment Maps

This week Aquatic Nuisance Control applied the general herbicide application of contact herbicides to singe down native aquatic plants that have reached nuisance levels in locations designated for control. We have published maps of these treatment areas below for your information. This treatment was applied to minimize recreational obsticles created by native vascular plants (mainly Illinios Pondweed) reaching the water surface. It is important to note that additional isolated spot treatments of herbicide and algaecide will likely be required as the summer progresses. We will post maps of these treatments as they develop. The following lakes were not treated at this time as they were not expressing nuisance levels biologically warrenting treatment: Camper Lake(s), Kitt Lake, Lily Pond, Rush Lake, Golden Pond, and Ranger Lake. These lakes may require spot treatments later in the season, if biologically warrented. Lost Canyon Lake has been classified as a "No Treatment" lake during the 2005 summer season. More detailed maps of the Main Lakes are available upon request.

Wild Celery is Driving Us Wild!!!

Over the past few weeks, we have been receiving phone calls and emails from some of you out there with various aquatic plant and algae concerns. One of the hottest sub topics under the aquatic plant control heading has been the control of Vallisneria americana, commonly known as Wild Celery (See image). Before discussing our plan of attack for minimizing recreational hindrances by this aquatic plant, I think we all need to understand what it is and why it has become such a headache for some of us.

What is Vallisneria?

Vallisneria americana is a native aquatic vascular plant considered to be beneficial by most authorities including Michigan State University and the University of Wisconsin.

Wild celery is one of the most sought after foods in waterfowl’s diet. Canvasback ducks are named after it, Aythya valisneria. Muskrats and swans love it too. The plants are considered good fish habitat as well. In 2004, most of the young of the year perch captured during seine netting were in and around the Vallisneria. Wild celery has ribbon like leaves attached to a “creeping” rhizome. A creeping rhizome! Sounds sinister! A creeping rhizome is basically a root that grows horizontally through the lake bottom sediment. Vallisneria over winters well via hardy tubers (just like potatoes) and roots. This is why wildlife is so found of this species, they store juicy nutrients in their roots. During the growing season, Vallisneria spreads into new areas via those “creeping” rhizomes. The little shoots growing off the creeping rhizomes can break off and float away to new locations to start new plants. In addition to this rhizome budding, Wild celery also takes advantage of sexual reproduction as a means of propagation, and this is where the headache begins. Adult plants are either male or female and they give rise to “curly-Q” peduncles during flowering, which typically occurs in mid summer. It is these curly reproductive shoots that get caught up in boat props and swimmers appendages. The plant itself is not a nuisance as it is low growing, occupying substrate that would otherwise be available for other plants. It is the reproductive shoots that cause the headache and it is the shoots we intend to control.

Where does Vallisneria grow?

Wild celery grows in firm (like imported beach sand and raked lake bottoms) sediment in ankle to six plus feet deep water (in some cases). In Canadian Lakes it tends to be found around bridge culverts and raked beaches. If you live on a lake other than the Main Lakes, you may not have noticed this plant. If you live near the boat launch and other isolated locations on the Main Lakes, you are all too familiar with this plant.

How did the Wild Celery come to be such an Issue?

A few of the emails we received mentioned Wild Celery not being present on their beachfronts in the past and that it seems to get worse every year. We do not have aquatic plant surveys from earlier decades to confirm this, but I believe it is true that the Wild celery is a new comer to the vascular plant community in our lakes. The plant was most likely introduced as seeds on the bodies or in the fecal deposits of waterfowl that frequent patches. It is critical to remember that Canadian Lakes is not a completely natural and balanced system. In most natural lakes in Michigan, balance has been achieved over thousands of years. Diversity develops year after year as new organisms compete against those that are already established in the lake. In an old diversified aquatic system, Vallisneria would have to compete with other low growing vegetation like Chara (actually a colonial algae), Elodea, Coontail, Naiad, and others. They would battle it out over time and each would find their own niche. They would have to compete with taller growing canopy forming aquatic plants like Northern milfoil and the Pondweed family too. By forming canopies, these plants shade out the low growers and thereby secure their niche in the lake. In the Canadian Lakes system, these canopy forming plants have been treated with herbicides as their canopies on the water surface represent a nuisance to some recreation. Because the Wild celery is a low grower with thick and resistant roots, it not only isn’t impacted much by contact herbicide treatments, there is a strong possibility these treatments actually favor the celery as it will be the first to be in a position to exploit new environments left open by canopy reduction from the herbicide treatments. A similar result is seen on raked lake bottoms. Once pre-existing vegetation is removed, the exposed lake bottom is waiting to be colonized. Vallisneria is most able to exploit this bare substrate because it can spread by rhizome creeping, budding, and sexual reproduction. When a homeowner rakes a lake bottom, the last plant they will be able to remove will be the deeply rooted, slender leaved Vallisneria.

So Summit Labs, what is the plan to control the nuisance created by Vallisneria?

During a recent discussion with Bill Huller of the University of Florida, one of the world’s leading aquatic plant control specialists, Mr. Huller was amazed that we were trying to develop control techniques targeting Vallisneria. At this point there is no textbook solution as this particular control requirement is very rare, but by brainstorming with experts like Mr. Huller and experienced herbicide applicators like our Norm Zion of Aquatic Nuisance control, we feel confident we can achieve increased levels of control over the nuisance reproductive shoots.

Our plan for 2005 will involve:

1. Having mapped nuisance locations in 2004, we can get a jump on the reproductive peduncles, treating the chronic areas before they arise.

2. We will have copper sulfate applied at low concentration in areas where non-targeted impact is a minimal risk.

3. We will have contact herbicides applied in areas the applicator believes they will be most successful.

4. We will consider and possibly experimentation with mechanical harvest, it success is demonstrated.

5. Most importantly, we will evaluate the level of control achieved by each technique so that as time goes forward, higher and higher levels of control will be achieved.

Because Vallisneria is a native plant very resistant to herbicides, we will not manage it for eradication. This would be highly irresponsible and ecologically damaging on our part. We will however focus control efforts on minimizing the nuisance effects created by the reproductive peduncle. That’s it for now. Hope you all get a chance to get out there and enjoy some water this week.

Your Lake Managers,

Joel Steenstra and Tom Krueger